The food we eat, who we eat with and the way in which we obtain it has a significant impact on our lives. Food has the power to bring joy, build connections and protect us from ill health yet many of us in Liverpool are struggling to access ‘Good Food.’ And whilst this was true even before the COVID-19 pandemic, this past year has created additional pressures on people and systems, surfacing unprecedented levels of food insecurity and disproportionately impacting some people more than others. The Covid-19 pandemic ‘stress tested’ the food system and brought to the surface some of the challenges that exist. It also surfaced the positive impact that communities can have in this space.

“Having spoken with several tenants struggling to make ends meet, the relationship between food and health is abundantly clear. In order to make their budget stretch, they are forced to purchase food items that are cheap, often processed and lacking in nutrition in order to put a meal on the table. This results in poor health or further amplifies existing medical conditions.”

Liz Boyle, Food Security Team Leader, Torus Foundation

“Access to healthy food should be a right, not a privilege. If we cannot afford enough good nutritious food it can often mean we are reliant on eating cheaper, higher fat, sugary and salty foods with low nutritional value. This can lead to excess weight gain, poor mental wellbeing and also increase our risk of developing long-term illnesses such as diabetes.

For families living with the added stress of low income, poor housing and education, and limited access to cooking facilities, this combined with a lack of nutritious food can make maintaining good health and managing existing illnesses even more challenging.

So families experiencing food insecurity often have several of these compounding factors making maintaining good health and wellbeing a lot more difficult. This is why the whole system needs to work together to tackle the complex and interrelated issues driving food insecurity faced on a daily basis by many of our families.

Melisa Campbell, Consultant in Public Health – Children and Young People

It is not okay that people do not have access to ‘Good Food’

It is estimated that 32% of adults in Liverpool are food insecure – where food is a source of worry, frustration, and stress (source).

Only 1 in 2 adults in Liverpool eat their five-a-day; (source) only 12% of kids aged 11-18 eat their five-a-day (NDNS 2021)

Liverpool is home to 3 of the 10 most economically deprived food deserts in England, areas which have 2 or less supermarkets and is in the most deprived 25% of areas (source).

An estimated 25% of women in the UK do not get enough iron in their diets (NDNS 2021).

An estimated 140,000 tonnes of food is wasted in the Liverpool City Region each year, producing approximately 368,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions each year, the equivalent of the CO2 produced by 80,033 cars in one year (source).

A survey of the menus of 26% of nurseries in Liverpool found them all to be deficient in energy, carbohydrates, iron, and zinc.

Around 14% of households experience fuel poverty which is significantly higher than the England average. Fuel poverty is a barrier to cooking (source).

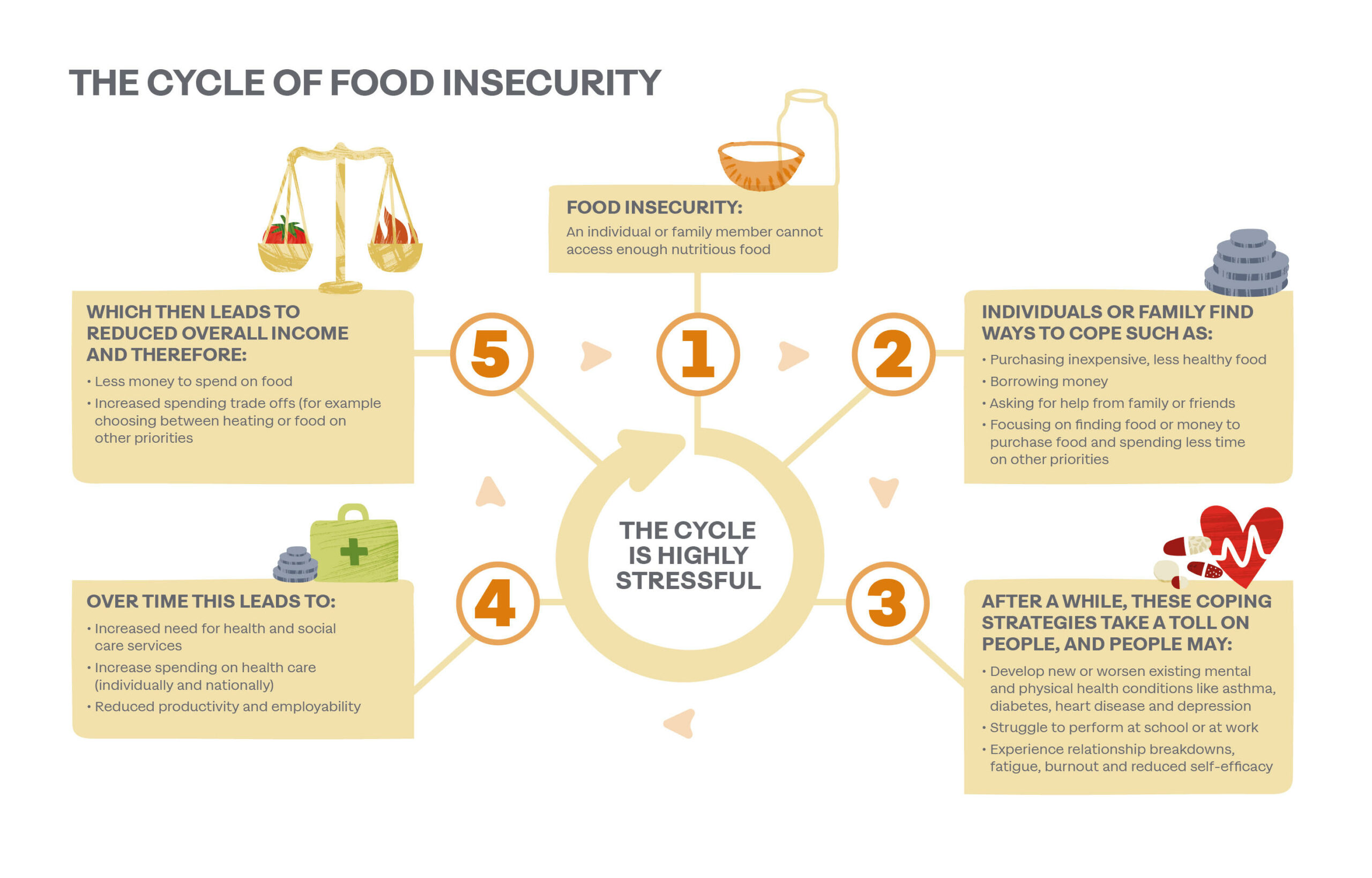

The vicious cycle of food insecurity

A lack of access to ‘Good Food’ is having a detrimental impact on people’s lives and people often become trapped in a vicious cycle illustrated below.

People can experience food insecurity at any age and these experiences can take a serious toll on people’s health and well-being (source).

The impact of food insecurity throughout the lifecycle

Access and uptake of ‘Good Food’ have the power of decreasing risk for diet-related diseases, improving mental and physical wellbeing, strengthening community connection and resilience, boosting creativity and productivity, stimulating economic activity, and reducing our carbon footprint.

Pregnancy:

- Stress

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Unhealthy levels of gestational excess weight

- Gestational diabetes

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Low and high birth weights

Childhood:

- Impaired academic performance and learning

- Experience of shame

- Behavioural challenges

- Decreased productivity (Source)

- Overweight and obesity

- Poorer physical health

- Poorer mental health and wellbeing

Adolescence:

- Impaired academic performance and learning

- Overweight and obesity

- Experience of shame and social isolation

- Depression, self harm and suicidal ideation

- Chronic conditions, particularly asthma.

Adulthood:

- Overweight and obesity

- Diabetes

- Poor diabetes management

- Mortality – Liverpool’s mortality rate from causes considered to be preventable is significantly higher than England’s (Source)

Older age:

- Chronic disease

- Poor management of chronic diseases

- Decreased health-related quality of life

- Malnutrition

These challenges are affecting some communities more than others

Among 30 to 79 year-old adults, diabetes is more prevalent in more deprived regions of Liverpool (NHS Mersey Care Data).

In Liverpool in 2019, the gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas was 11.1 years for men and 8.9 years for women (PHE Local Health Profile 2019).

Children in deprived communities are more than 1 cm shorter on average than children in wealthy communities by the time they reach age 11- lower heights are a reflection of long term malnutrition (Broken Plate Report).

The most deprived regions of Liverpool have fewer supermarkets and more convenience stores than less deprived regions (source).

During the Covid-19 pandemic adults who are self isolating, extremely clinically vulnerable, with a disability or a limitation, on low income, with children eligible for free school meals were more at risk of food insecurity (source).

Children in the most deprived areas of Liverpool are 40-50% more likely to have excess weight (NCMP data 2010-2018).

The poorest 20% of UK households would need to spend 39% of their

disposable income on food to meet Eatwell Guide costs. This compares

to just 8% for the richest 20% (Broken Plate Report).

Our time is now

We see this time as a pivotal moment in history; a time of significant change and challenge and a real need to work together to create real change. We know that doing the same thing that we did before is not an option and we are working towards a brighter future, where everyone in Liverpool has an equitable chance at reaping the benefits of eating Good Food. It’s time for us to come together to bring our vision of ‘Good Food’ to life.

Join the Good Food Liverpool movement